The family tragedies that preceded us

Looking back on my husband's family history and how it echoes where we are today

May is a month of both birthdays and mourning in my extended family. There are the birthdays of my elder stepdaughter, my two sisters-in-law and my niece, and the yahrtzeits — the anniversary of the deaths — of my father-in-law and sister.

So there are weeks of cemetery visits and the brunches that usually follow, as well as beach days (at least this year) and birthday dinners. That’s a good thing right now, given that I find it helpful to be with people, to have these moments of normalcy amid the insanity, sorrow and confusion of these times.

On Friday, we marked the 17th yahrtzeit of my father-in-law, Leopold ‘Poldi’ Laufer, who died in 2007 after a long illness that included debilitating dementia over the course of at least 15 years. I didn’t really get to know Leo well, as he was already sick when Daniel and I met and married, a shell of the person he had been.

I’ve gotten to know more about him through the stories, letters and writings that we read and discuss each year around his yahrtzeit. He was a runner, the kind of person who loved fresh bread and smelly cheeses, hiking and skiing, and spent a lot of his professional life working in the international development world.

This year, we stood around his grave — actually, around someone else’s grave in Jerusalem’s Har Menuchot high-rise cemetery, as one of our family friends needed flat ground and shade on the hot Friday morning — and Daniel read a letter that middle-aged Leo had written to his son, Daniel’s brother Michael in April 1973, 50 years ago, just months after the Yom Kippur War.

It was the second letter that Daniel read, from his own grandmother, known as Babi, the Czech moniker for grandma, Leo’s mother, written to the same brother, Michael, that really gave me pause.

Babi, her husband Robert, daughter Hanna and Leo, were refugees who escaped Czechoslovakia during the war. Leo’s father, Robert, had left Czechoslovakia first in March 1940, aiming to set things up for the family, and it was May 1940 when Babi, Hanna and Leo left, making their way through Germany, Italy for a longer period, with short stops in Spain and Portugal and then to Cuba for three months before finally making it to New York on December 26, 1941 in a complicated, nerve-wracking and probably at times terrifying journey that took months. Leo was about to turn 16 when they finally arrived after their year-and-a-half long journey.

It was his sister, Hanna, six years older, who guided their unit through that harrowing time.

They settled into life as immigrants, living in Jackson Heights, Queens and at some point a few years later, Hanna, then 28, met a man named Jesus Monleon.

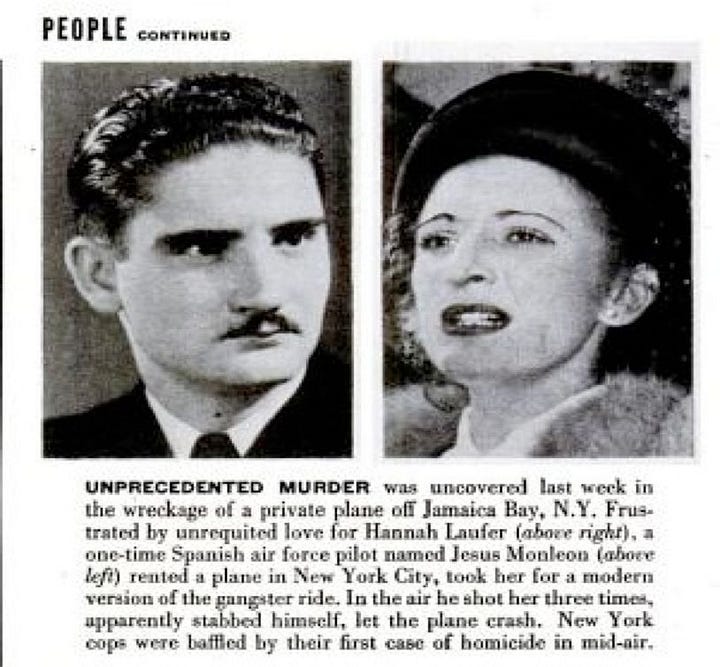

He was a Spanish pilot who had fought in the Spanish Civil War and then in World War Two, was separated from his wife but not divorced, and somehow, he and Hanna had met. She had reportedly broken up with him weeks earlier, and in a last-ditch effort to reconcile with her, the two went up in a rented plane where he shot her three times and then stabbed himself, a murder and suicide before the plane crashed, and both were declared dead.

It’s a terrible, tragic story that we talk about sometimes, having gained a few more details from articles in the New York Times archives about the incident. The main article, oddly enough, is from September 18, 1948, my birthdate just twenty years earlier and four months after the declaration of Israel’s independence. That timing feels momentous, too.

On Friday, we stood around talking about Babi, Daniel’s grandmother, the mother of Hanna, who escaped Nazi Europe, made it to the US, with the guidance of her daughter, only to lose her to a terrible tragedy. Babi, Daniel’s grandmother, is often described in the family by the dementia she experienced in her old age, and how she needed Hanna, her child, to guide her out of Europe. But one can only imagine what it was like to survive all those tragedies and losses, and for her to try and rebuild her life into something new.

Our niece Noa, Hanna’s great-niece, a social worker and lawyer who’s been working with Nova survivors since October, pointed out that Hanna herself was also a survivor, although the family didn’t think of themselves that way, not having gone through the concentration camps. But she survived escaping her country, making her way across the world, bringing her mother and younger brother safely to the US, and then establishing herself in a new place.

We don’t know much about what led to her relationship with this Spanish pilot, who joined the Royal British Air Force and had his own World War Two experiences.

It’s all a tremendous tragedy when you think about how Hanna Laufer survived so much, and who she could have been. She was dead at 28, leaving her younger brother, Leo, then 22, as the only child to his parents, immigrants to a new land, determined to make something of his life and to carry on as his parent’s only living child.

My niece commented it wasn’t all that surprising to think that Hanna Laufer would have made some questionable choices after everything she went through as a young woman, as she struggled to figure out who she was after everything she saw and experienced. It’s something she sees in the young women she works with now, as they try to make sense of the horrors of October 7, of their own survival and the deaths of all those who didn’t make it.

And for the rest of us, as we think about what our parents would have thought of the last months, of the tragedies and losses and hostages, of the antisemitism and protests and rhetoric, we also think about how they weathered the events and tragedies of their time and how we’ll weather our own, guided by their examples.

We marked the anniversary of the death of my father-in-law in between Holocaust Memorial Day on the preceding Monday, and before Memorial Day and Independence Day this week, dates that resonate for us and resonated for him, and that take on a different kind of meaning even now, so many years after his death.

*Thanks to my brother-in-law Peretz Rodman, lover of words and history of all kinds who helped me with the details of this family story.

My Mother worked for Hannah’s cousin ( I think she was a cousin) Ruth Press in London. She was moving to a smaller apartment and was going to throw it away and I didn’t want it to go in the skip. Hannah must have spent a lot of time making it. Not sure, but I like to think she was telling a story when you follow the spiral round. I can’t attach the pictures. Do you have an email address or WhatsApp that I can send to?

Hi Jessica, I have a pottery art work by Hannah dated 1948. I’ll send you some pictures if you like.