I thought I was dreading October 7 and the chagim, the Jewish high holidays, but now I realize, with a pit in my stomach, how I’d like to go to sleep before lighting candles for Simchat Torah, the Hebrew date for the Hamas massacre that took place on this date last year, and wake up when it’s all over.

I only started thinking about this in real time yesterday morning, the day after Yom Kippur. It’s usually a day of recovery of sorts, as you get to drink coffee again, thank goodness, and as it was Sunday, it was also the first day of the work week. This week, it’s a shorter one, knowing that come Wednesday, we’ll be preparing for another holiday, for Sukkot, usually the lighter end of the high holidays, with its simple huts and decorations, palm fronds and citrons, held for shaking and rituals.

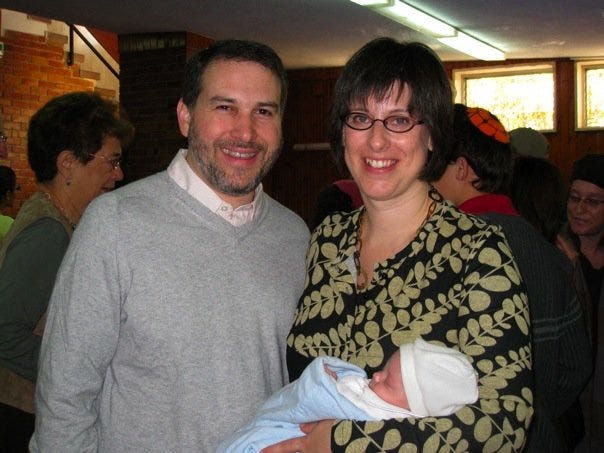

My twin teenage sons were born on erev Sukkot, Sukkot eve, six weeks early, and even though I begged my doctor to give me a few more days before their C-section — we were supposed to have the family over for my mother-in-law’s beer beef bourguignon, full of pearl onions — she said no way, and our boys were born at 11 am that day. It’s become a celebratory time of year for us, usually bookended by the Hebrew and secular dates of their birthday, and we celebrate a lot of it in the sukkah.

It’s funny, because I’m not much of a Hebrew date person. Israelis, even secular Israelis, mark a lot of calendar dates with the lunar Hebrew calendar that is parallel to the secular calendar but isn’t exactly aligned with it. They may celebrate their Hebrew birthday rather than their secular one, or their anniversaries on the Hebrew date. Jewish holidays are primarily marked by the Hebrew date, and commemorative dates as well.

When bereaved families and the government began discussing ceremonies for October 7, that made sense to me. We keep saying and writing October 7, that’s the date that’s imprinted on our minds. And on October 7, last week, there were multiple ceremonies, including the official government one that was pre-recorded, the alternative one in Tel Aviv, many held at the kibbutzim in the south.

But as we began planning for Sukkot in my house yesterday, cleaning up our deck, inviting some friends and family over for various meals, I was suddenly confronted with the eight days of this holiday. I saw a red square around October 24, the secular equivalent of Simchat Torah and I realized, that’s the day that will resonate most for me, for so many people, the bereaved and the hostage families, the survivors and the injured — any and all of us.

I get it. In our theocracy, we can’t hold ceremonies on a holiday, and it’s logistically tough to do so, even on the evening when the holiday has ended in the early evening hours. Kibbutz Yad Mordechai in the south, which was attacked on October 7 but miraculously untouched, is holding a ceremony next Thursday night, but it’s a smaller affair, for those directly affected by the attack on that day. (As I write this, there’s been an announcement that there will be a state ceremony on October 27, three days later, and organized by Transportation Minister Miri Regev, a Netanyahu ally and someone many Israelis love to hate.)

But what will the rest of us do on that day? I’m part of the Jewish world that goes to synagogue and dances — literally — with the Torah, taking shots of whisky and generally reveling in the day. I didn’t do it last year, when it fell on October 7. That day, we sat at home, first sheltering from the rockets and then watching with horror what was unfolding in the south, at the small towns and kibbutzim, at the Nova party. I was working by the afternoon, something I really never do in my Shabbat-observant life.

And this year? I don’t know. There are discussions being held in many synagogues around the world about what to do — does one dance to defy Hamas, to move forward in our lives, or mourn, defying any kind of celebration on the day when more than a thousand people were killed, tortured, raped, assaulted, dragged into Gaza.

I’ve danced at weddings in the last few months, but I don’t want to dance on October 24, Simchat Torah and one year to last year’s devastating attack.

I’m looking for some answers, and I’m turning back to one of the sermons my father, Rabbi Ted, wrote back in 1987. My siblings and I have taken to printing out those sermons, printed on his dot matrix printer back in the day, reading them during the long days of prayer of Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur.

We read one sermon that he wrote about Sukkot 37 years ago, as he was speaking about the differences between religious and non believers, those who see order and meaning in life and those who see only chance events.

He quoted philosopher William Barrett, paraphrasing it like this;

“Life is full of misery, disorder and chaos. The earthquake that kills 1000s of people. Hurricanes. Sickness. Terror bombings kill the perpetrator and the innocent. Bad things happening to nice as well as wicked people all the time. It's very tough to see order and meaning beyond the chaos.”

(We’ve discussed all year long what our parents would have had to said about this past year, besides the sorrow and anguish they would have felt.)

He posited that the chag, the holiday of Sukkot, comes along after the high holidays to see the meaning beyond the chaos, to tempt us, to arouse and stimulate our feelings for nature and the earth’s productivity, by having us build or visit a sukkah, to watch the mingled shadow and light stream through the schach, the makeshift roof of the sukkah, built with branches.

I can appreciate the idea and know that it’s something I usually do on Sukkot. I’ll be honest: I’m okay with building our sukkah, but having a hard time thinking of decorating it. I looked at three little succulents I bought last year for the sukkah, and this morning planted them in one of the planter beds in our garden, looking for permanence rather than decoration.

It was a task, a touch of nesting, and those short tasks, 20 minutes of clearing out a drawer or sweeping the deck for the sukkah, is something I can wrap my head around, setting some order to the chaos around me. Hopefully sitting in the sukkah is something I think I will be able to do, throughout this holiday. I know that I’m one of the lucky ones to be able to sit and think, that I’m not mourning, not in anguish. I’m hoping that my thoughts and ruminating can somehow help those in deep pain — because right now, that, along with looking forward, is what we’ve got.

I think some of your father's ideas can also found in Sefer Kohelet. And I think we're looking for the cracks that let the light in.

Sigh. This resonates in so very many ways. May you- and all of us - find spots of joy to hold onto, in between this new reality of terribility. We are all mourning in some way and yet I feel desparately that we must build hope along with our sukkot.